An Uphill Battle

October 11, 1994

JIM WASHBURN | SPECIAL TO THE TIMES

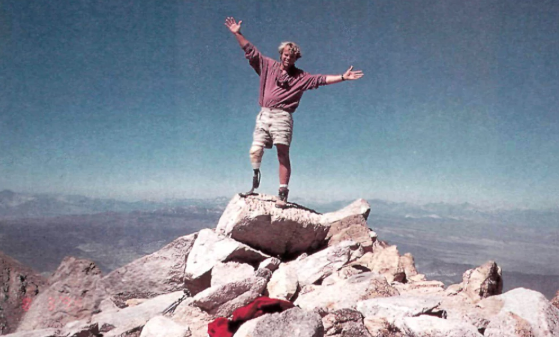

An Uphill Battle: Todd Huston, whose right leg was amputated 12 years ago, has an artificial limb for everyday use, but on special occasions, he uses the one that lets him move mountains–by climbing them.

IRVINE — Todd Huston has three right legs. There’s the phantom one, the leg he still senses as being there, though it was amputated 12 years ago. “I can still tell you exactly where each of my toes is,” he says.

There is his everyday leg, with a flesh-toned exterior and cosmetic toes. And then there is his mountain climbing leg, a bare graphite, metal, and fiberglass Terminator-looking appendage with a boot’s Vibrum sole glued right to the heel. That sole is worn and crumbling at the edges, as one might expect of one used in setting a world record.

We were talking at the Sports Club, Irvine, where Huston trains. Earlier this year Huston, 33, scaled the highest point in each of the 50 states in 66 days, beating the previous record of 101 days set by an able-bodied man in 1990.

Some of those summits were downright comical, such as Britton Hill, which at 345 feet above sea level is the highest spot in Florida. Then there’s Delaware’s dimple of a peak, Ebright Azimuth, “which happened to be in the middle of a street, right outside of Wilmington,” Huston said. “But it took us several tries to get a picture there because there was so much traffic.”

At the other extreme was Alaska’s Mt. McKinley, the highest point in North America and 20,320 feet of mean. Huston was climbing in minus-35 degree weather there, while Texas’ Guadalupe Peak was scaled in 118-degree heat. On other heights, he was beset by biting black flies or high winds. Just getting from climb to climb was an effort, often driving 500 miles a day, and sometimes rerouting to dodge tornadoes.

It’s a trek that few complete, only 37 including Huston to date. He is the first one-legged man to attempt it. Rather than dwell on the hardships his unique status imposed, he prefers to joke about the advantages. “I only had five toes to worry about getting frostbite.

I only had to worry about one ankle twisting. My right calf muscle never got sore. So I had a leg up on other climbers. Did I ever feel de-feeted? No,” he said.

Huston, a Balboa Island resident, is a psychotherapist who is a clinical director of the Amputee Resource Center at Brea’s NovaCare Orthotics and Prosthetics, helping amputees to deal with the trauma of limb loss.

Huston’s own trauma began at age 14 when he was water skiing with his family in Oklahoma. He had been in the water untangling the ski rope when the family’s boat slipped into reverse.

“I was yelling ‘Stop the engine,’ but no one could hear me, and I had one of these big heavy water skiing jackets on and couldn’t swim, so the boat hit me, and it sucked both my legs into the propeller,” he recalled. “When they pulled me out of the water there was blood squirting six to eight feet out of my body. My left leg was completely open and the whole backside was missing from my right leg.”

A nerve had been severed in his right leg, paralyzing it. Doctors told his family he probably wouldn’t walk again. A month and a half later he was barely able to walk out of the hospital “on legs like spaghetti noodles.”

By the time he was in college, the reduced circulation in his paralyzed leg caused it to become infected, resulting in lengthy hospitalizations that often kept him from attending classes or working.

“After a whole series of operations, that eventually led to the decision to just amputate the leg. So at age 21, I chose to have my leg amputated because what I wanted was to have a life and a lifestyle over a leg.

“It’s a very tough decision because it’s permanent. You can’t do it and go, ‘Oops, wrong decision, let’s go back.’ I knew I’d have to live with it for the rest of my life.

“When they did it I was wide-awake on the operating table, with not even an aspirin in me, for two reasons. One: I wanted to feel I had more control over the situation than my disease did, and two: If you’re anesthetized, after surgery you can’t eat pizza. And I love to eat pizza after surgery. So after I had my leg amputated I went back to my room and ate pizza.”

Huston wore a conventional prosthetic leg for a decade, which permitted him to live a productive life, though not a physically active one. “I could not take more than four or five running steps without tremendous pain and couldn’t walk over half a mile at any one time. At night I’d have these vivid dreams about running in a field.”

After breaking a couple of conventional legs with his exertions, two years ago he got his insurance company to spring for a new leg, called a Flex-Foot manufactured in Aliso Viejo. Its design, which includes a shock absorber and spring-like flexible graphite, responded more like a real limb.

“Initially I could only run about 100 feet with it, I was so out of shape. I called everybody I knew the day I was finally able to run all the way around Balboa Island. After three months I was able to run all the way to Laguna and beyond.”