An Uphill Battle

October 11, 1994

JIM WASHBURN | SPECIAL TO THE TIMES

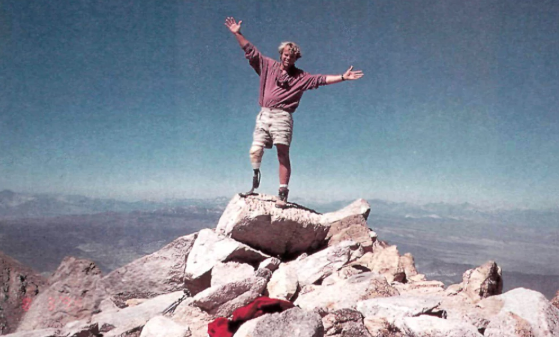

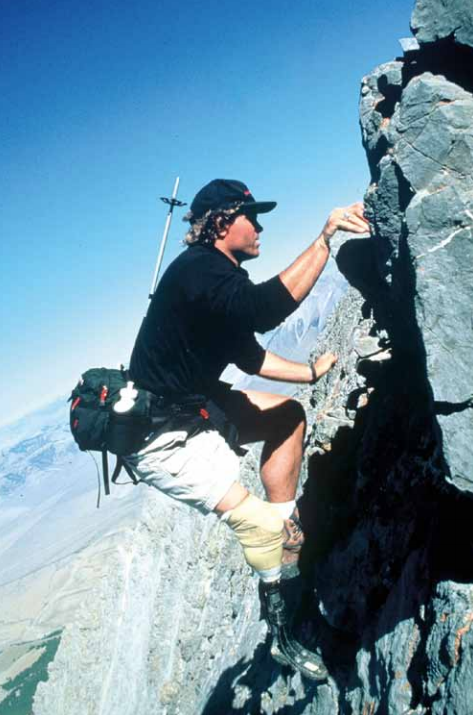

An Uphill Battle: Todd Huston, whose right leg was amputated 12 years ago, has an artificial limb for everyday use, but on special occasions, he uses the one that lets him move mountains–by climbing them.

IRVINE — Todd Huston has three right legs. There’s the phantom one, the leg he still senses as being there, though it was amputated 12 years ago. “I can still tell you exactly where each of my toes is,” he says.

There is his everyday leg, with a flesh-toned exterior and cosmetic toes. And then there is his mountain climbing leg, a bare graphite, metal, and fiberglass Terminator-looking appendage with a boot’s Vibrum sole glued right to the heel. That sole is worn and crumbling at the edges, as one might expect of one used in setting a world record.

We were talking at the Sports Club, Irvine, where Huston trains. Earlier this year Huston, 33, scaled the highest point in each of the 50 states in 66 days, beating the previous record of 101 days set by an able-bodied man in 1990.

Some of those summits were downright comical, such as Britton Hill, which at 345 feet above sea level is the highest spot in Florida. Then there’s Delaware’s dimple of a peak, Ebright Azimuth, “which happened to be in the middle of a street, right outside of Wilmington,” Huston said. “But it took us several tries to get a picture there because there was so much traffic.”

At the other extreme was Alaska’s Mt. McKinley, the highest point in North America and 20,320 feet of mean. Huston was climbing in minus-35 degree weather there, while Texas’ Guadalupe Peak was scaled in 118-degree heat. On other heights, he was beset by biting black flies or high winds. Just getting from climb to climb was an effort, often driving 500 miles a day, and sometimes rerouting to dodge tornadoes.

It’s a trek that few complete, only 37 including Huston to date. He is the first one-legged man to attempt it. Rather than dwell on the hardships his unique status imposed, he prefers to joke about the advantages. “I only had five toes to worry about getting frostbite.

I only had to worry about one ankle twisting. My right calf muscle never got sore. So I had a leg up on other climbers. Did I ever feel de-feeted? No,” he said.

Huston, a Balboa Island resident, is a psychotherapist who is a clinical director of the Amputee Resource Center at Brea’s NovaCare Orthotics and Prosthetics, helping amputees to deal with the trauma of limb loss.

Huston’s own trauma began at age 14 when he was water skiing with his family in Oklahoma. He had been in the water untangling the ski rope when the family’s boat slipped into reverse.

“I was yelling ‘Stop the engine,’ but no one could hear me, and I had one of these big heavy water skiing jackets on and couldn’t swim, so the boat hit me, and it sucked both my legs into the propeller,” he recalled. “When they pulled me out of the water there was blood squirting six to eight feet out of my body. My left leg was completely open and the whole backside was missing from my right leg.”

A nerve had been severed in his right leg, paralyzing it. Doctors told his family he probably wouldn’t walk again. A month and a half later he was barely able to walk out of the hospital “on legs like spaghetti noodles.”

By the time he was in college, the reduced circulation in his paralyzed leg caused it to become infected, resulting in lengthy hospitalizations that often kept him from attending classes or working.

“After a whole series of operations, that eventually led to the decision to just amputate the leg. So at age 21, I chose to have my leg amputated because what I wanted was to have a life and a lifestyle over a leg.

“It’s a very tough decision because it’s permanent. You can’t do it and go, ‘Oops, wrong decision, let’s go back.’ I knew I’d have to live with it for the rest of my life.

“When they did it I was wide-awake on the operating table, with not even an aspirin in me, for two reasons. One: I wanted to feel I had more control over the situation than my disease did, and two: If you’re anesthetized, after surgery you can’t eat pizza. And I love to eat pizza after surgery. So after I had my leg amputated I went back to my room and ate pizza.”

Huston wore a conventional prosthetic leg for a decade, which permitted him to live a productive life, though not a physically active one. “I could not take more than four or five running steps without tremendous pain and couldn’t walk over half a mile at any one time. At night I’d have these vivid dreams about running in a field.”

After breaking a couple of conventional legs with his exertions, two years ago he got his insurance company to spring for a new leg, called a Flex-Foot manufactured in Aliso Viejo. Its design, which includes a shock absorber and spring-like flexible graphite, responded more like a real limb.

“Initially I could only run about 100 feet with it, I was so out of shape. I called everybody I knew the day I was finally able to run all the way around Balboa Island. After three months I was able to run all the way to Laguna and beyond.”

Amputee sets world record in climbing

By Teri L. Hansen

Staff Writer

Sep. 15, 2014 @ 11:23 am

MOUNDRIDGE

At 14, Todd Huston died twice.

After a traumatic boating accident, doctors battled to save his life and revive him after he was clinically dead two times. They succeeded both times.

After years of trials, turmoil, and challenges, Huston has become a world-renown inspiration. Thursday night the residents of Moundridge were given the chance to meet this author and motivational speaker at the annual Chamber of Commerce dinner.

“This is life for me,” Huston said. “When I’m not traveling and speaking is when it’s hard for me.”

During a water-skiing trip in eastern Oklahoma, Huston found himself in the water with the boat holding his family and friends backing up toward him. Despite his frantic yelling, no one could hear him, and he was hit, his legs sucking into the propeller. After being thrown around by the powerful propeller, his father reached into the bloodred water and pulled him out. His legs were mangled.

“I thought at the time, ‘Why?,’ Huston said. “Why is this happening to me?”

At the dock, there happened to be a doctor and nurse who gave him first aid and called an ambulance. At the first hospital, he was sent to, the emergency room doctor was overheard telling his staff, “I don’t think this kid is going to make it.”

From there he was transferred to a larger facility where he died on the operating table, not once, but twice. When he woke up, he found his right leg didn’t have any skin on the back. After sewing his hand to his leg to increase blood flow, they grafted skin to his leg and covered him in a body cast.

After spending time in a wheelchair, on crutches and in a metal brace, it was clear that his body wasn’t going to be the same. His right leg was paralyzed everywhere below the knee. The former teen athlete now had a leg that was, for lack of a better word, useless.

“I was always playing football as a kid,” Huston said. “Now I couldn’t even sit in a chair at school for too long, because my spine stuck out from all the weight I had lost.”

For seven years, Huston struggled with a leg that no longer listened to him and worse. It was no longer able to tell him when something was wrong. He would step on nails or glass and not feel it. He’d get home, take his shoe off and find a bloody, mess. Eventually, he battled infections.

“It was pretty disgusting,” Huston said.

At 21 years old, Huston had his leg amputated in order to save his life, as the infections were taking their toll. With only localized numbing below the waist, Huston had his leg removed below the knee, without anesthesia.

That’s when I realized that, in one way or another, everyone has challenges,”

Huston said, “but those challenges are really opportunities — opportunities to find out what you are truly made of.”

The first step on his prosthetic leg, which was not as advanced as prosthetics are now, was excruciating. Of course, for the pain, doctors prescribed him painkillers. After a couple of years, he found himself addicted to those painkillers. His addiction came to a head one day when he found himself believing he had overdosed. In that moment, he asked God for a chance to make it right.

He didn’t overdose, and since that day, he has taken only two painkillers in his life — one after having his wisdom teeth removed, and one after he twisted his one remaining ankle. He doesn’t drink alcohol or even soda pop.

“The decision to change something in your life is only one moment away,” Huston said. “Live your life moment by moment by moment with passion.”

Huston went to grad school and became a psychotherapist. While working in California, he met a woman. They married quickly because she was from New Zealand, and there were immigration issues to consider. After two years of marriage, once she had received her citizenship, Huston came home to find her gone. They had agreed to move prior, so he had quit his job and already had given notice they were vacating their home. He was left with no wife, no job, no home, and his bank account had been cleaned out.

“All in one week,” he said. “So I guess you can say I had a pretty rough week.”

Shortly after he received a letter from Chicago requesting him to be a part of a team of people who had disabilities who were going to climb the highest elevations in all 50 states. He began training immediately. After 16 years of not running, he began running again.

“I discovered something about running,” he said with a laugh. “I hate it!”

One month before the expedition was set to start, it was canceled. Huston still wanted to do it, so he decided to raise the $50,000 necessary for him to go. John Shanahan, the owner of Hooked on Phonics, heard about the expedition and was impressed. He donated all of the money necessary for the trip.

So off Huston went. Every state, every elevation. From the highest point in Delaware, in the middle of a street, to the 23,323-foot Mt. McKinley in Alaska. And yes, even Kansas.

“Which wasn’t that difficult, I’ll tell you,” he said.

He encountered wild animals on his journeys, such as bears, rattlesnakes, and wild horses. He suffered sunburns in places he thought couldn’t be sunburned, such as the roof of his mouth. He slept in a tent and burrowed into the snow for shelter from blizzards and avalanches. In his home state of Oklahoma, he found a class of fifth-graders waiting for him at the top of Black Mesa to cheer him on and hear his story.

Huston not only did what many thought was impossible, but he also did it fast. Really fast. The previous record-holder, Adrian Crane, climbed the 50 states in 101 days. Huston did it in 66 days, 22 hours and 47 minutes, making him the new record holder. Not only that, he is now the only disabled person in the world to break an able-bodied sporting record. It was tough, frightening and chaotic.

“Fear is not real, it only exists in your mind,” Huston said. “Fear nothing and love all. Love will make you climb mountains.”

Huston has been on CBS, NBC, ABC, CNN, TBN, C-SPAN, Inside Edition, Extra and Robert Schuller’s Hour of Power. He’s been featured in Sports Illustrated, L.A Times, Wall Street Journal and Forbes. He is the author of “More Than Mountains: The Todd Huston Story,” which is being adapted into a screenplay. For more information on Todd Huston, visit www.toddhuston. com.

Read more: http://www.mcphersonsentinel.com/article/20140915/News/140919587#ixzz3EB0EZ2pb

Sports Illustrated Interview

Sports Illustrated

BY KEN MCALPINE

May 28, 1995

In the cold half-light, the snowflakes dropped, soft and only partly formed, while Arctic winds plucked at and slapped the dome tent. Inside, condensed breath that had frozen on the nylon ceiling during the night loosened and fell onto four sleeping bags and the climbers inside them.

One of the climbers, Todd Huston, was awake, and reels were running through his head: a fellow climber disappearing into a crevasse right on the airstrip. Another climber, just back from a failed attempt on the summit, dully describing the glove he saw locked in the ice, the owner’s hand still tucked inside, the glove’s design 20 years old. A rescue team discovering two Koreans who had been surprised by a storm, one of the men dangling upside down from his rope, the other sitting on a rock and holding a radio next to his head, both men frozen.

Later that morning, in the blue-white glare of early day at 17,200 feet, Huston was readying himself for what he hoped would be a push to the 20,320-foot summit of Mount McKinley in Alaska’s Denali National Park. Earlier, expedition leader Mike Vining had told Huston, “This will be the hardest day of your life.” Vining, 44, is a no-nonsense sergeant major in the Army with forearms so developed he is nicknamed Popeye. He was not impressed with Huston. “He had no prior mountaineering experience,” Vining would say months later, recalling the climb. “He had no winter camping experience. He had no idea what he was doing. That seemed an unusual background for a serious climb.”

No surprise, then, that Huston was obsessed with death, specifically his own. He thought about dying often as he and his team inched their way up Mount McKinley last summer, launching a madcap, record-breaking 67-day spree in which Huston climbed to the highest point not only in Alaska but also in each of the other 49 states. Huston knew more than he wanted to know about death, having already almost died in a serious accident 20 years earlier. This had made him cautious–and willing to admit that he was frightened.

“I must have asked a jillion questions on the way up McKinley,” says Huston. “If we do this, can we die? Can we slide into a crevasse and never be seen again? Basically I went up that mountain whining every step of the way.”

There’s no hesitation or whining today. Huston, 34, whips his Ford Taurus into the most convenient parking space. He peers up at the handicapped sign and shuts off the car. He begins to assure you that during his cross-country high-points blitz he never once parked in a handicapped spot, but Huston has a nagging conscience. “Well, maybe once or twice,” he says. “You park in a handicapped spot and go climb a 13,000-foot snow-and-ice mountain, and then you get back, and you’re like, ‘Gee, I’m sure glad I don’t have to walk across the parking lot.’ ”

Should he be accosted for allegedly parking illegally, Huston can simply roll up the right leg of his pants, as he does later this afternoon when he plops down on the couch in his apartment in Newport Beach, Calif. “Man, I’m sore,” he says, rubbing his thigh just above the knee, then removing the lower part of his leg and setting it next to him on the couch. He regards the appendage briefly and with disdain.

“I have another leg that’s a lot more comfortable,” he says. “But my good leg is in the shop.” Surveying his right thigh, he says, “There’s the actual stump that climbed McKinley.”

And McKinley was only the beginning. Huston’s high-peaks adventure claimed its first victory last June 1, when he stood atop Mount McKinley’s South Summit, and its last on the morning of Aug. 7, when he drove most of the way up Hawaii’s Mauna Kea. Huston broke by 34 days the record set in 1990 by Adrian Crane, a mountaineer who walks about Modesto, Calif., on two legs. Huston’s task was dubbed Summit America, and with it behind him he is moving on to grander things. On April 12 he climbed Australia’s 7,310-foot Mount Kosciusko, launching a journey that he hopes will eventually see him reach the high point in each of the world’s 186 countries. That shopping list includes some horrifying heights: Argentina’s Aconcagua (22,831 feet), Antarctica’s Vinson Massif (16,864 feet), Russia’s Mount Elbrus (18,510 feet) and Nepal’s Mount Everest (29,028 feet), peaks that have stymied, and killed, plenty of adventurers. Those were able-bodied climbers. And Huston is … well, ah, you know…

“Amputee, disabled, handicapped, physically challenged, a one-legged gimp,” says Huston. “I don’t get caught up in this politically correct stuff.”

To understand Huston it helps to know that he had a rough go of it from the start. He was born with a cleft lip and palate, which made it difficult for him to eat. He had his first ofseveral operations at six months to repair the cleft palate, and at two years he had the first operation to repair the lip. But all of this paled in comparison to what followed.

Huston was 14 that humid summer day on Lake Tenkiller, near his home in Tulsa. He was bobbing in the water after a ski run when the family motorboat slipped into reverse. Before anyone realized it, Huston’s legs were in the propeller. His father, Bill, grabbed every available towel, and Todd’s little brother Scott, who had never driven a boat before, flung the vessel at the nearest dock. Miracle of miracles, a doctor and nurse happened to be on the shore.

The damage to Todd’s left leg was severe; his right leg was nearly cut off. Doctors had to resuscitate him twice, once in the emergency room and once on the operating table. The doctors saved his life and both his legs, but the propeller had severed the sciatic nerve in his right leg, paralyzing his foot.

There followed seven years of operations and pain. His left leg eventually healed, but an infection started in his right foot and grew doggedly worse. At one point, hoping to provide a steady supply of blood to failing skin grafts on his right leg, doctors sewed Todd’s right arm to the back of the leg, splicing arm veins to those in his leg. Somehow Todd’s family–mother Barbara, younger brother Stephen and younger sister Jennifer in addition to Bill and Scott–put a normal spin on life at home. “Todd never had the feeling he was handicapped in our family,” says Bill, a straightforward man who runs his own wholesale lumber business. “Of course, he handled it all so well, we never had the feeling he had been hurt.”

Todd was 21 when he had the final operation on his leg. His useless right foot caused him constant pain, and the infection threatened to spread into his lymph nodes. This probably would not have killed him, but it would certainly have spread the pain throughout his body. He decided to have his right leg amputated below the knee. He also opted to remain conscious during the operation.

“I wanted to feel I had control over the situation,” he says. “Plus, if you’re anesthetized, after surgery you can’t eat. And I love to eat pizza.”

He has never regretted his decision to remove the leg. “Took care of the infection,” he says. “Cleared it right up.”

Huston’s campaign to climb the high points in all 50 states began almost by accident. In the summer of 1993 Huston, who has a master’s degree in counseling psychology from National University in San Diego, was working as the clinical director of the NovaCare Amputee Resource Center in Brea, Calif., when a pamphlet arrived on his desk. A group from Chicago wanted to organize a 50-state high-points expedition with several physically challenged people. Did Huston know anyone who would be interested?

He did. And when the group’s plans fell through the following spring, Huston decided to go it alone. No matter that he had never done any climbing. He trained by running. He ran 20 feet, then 100. He snapped legs. He fell. He sprawled across benches, exhausted. Within three months he could run 12 miles. He talked PacifiCare Insurance into buying him an $8,000 climbing leg complete with a shock absorption system and a Vibram boot sole (”It goes squishhh when you walk,” Huston says). He joined a tony health club with a climbing wall and other noteworthy perks (”The women are phenomenal”). He talked Whit Rambach, a guide originally hired for the Chicago project, into coming along with him. He talked sponsors into supplying money, from nickel-and-dime checks to $40,000 from John Shanahan, the CEO of Hooked on Phonics. Huston talked his parents into providing their blessing and the family pickup truck, in which he and Rambach bombed about the country, covering 35,000 miles altogether. Huston possesses the two essential tools of the empty-pocketed adventurer: charm and pigheadedness.

Hardest of all, Huston talked himself up some daunting mountains. Sure, there were some yuks during the quest. Conquering Florida’s high point–Britton Hill, 345 feet–entailed a 30-yard walk. Summiting Delaware’s Ebright Azimuth meant dashing out to the middle of a busy road. The high points of Tennessee, both Carolinas, Alabama and Georgia were notched in a day. “Remember, we said high points,” says Huston. “We didn’t say mountains.”

But there were some imposing mountains too–Montana’s Granite Peak, Washington’s Mount Rainier, Wyoming’s Gannett Peak, Oregon’s Mount Hood, Nevada’s Boundary Peak and Alaska’s McKinley are all at least 11,000 feet high.

Climbing with an artificial leg poses special problems. It requires more energy than climbing with two healthy legs, for example, and thus Huston, a thorough planner, embarked on the more serious climbs sporting 10 pounds of additional chunk on his 188-pound frame (“Who lived on Donner Pass? The fat people,” he says). And despite its shock absorption system, Huston’s climbing prosthesis pressed at his stump, especially during descents. “By the end of the day,” says Vining, “he had extra pain that the rest of us didn’t have to deal with.”

Now confident of Huston’s abilities, Vining will accompany Huston when he attempts to climb Tanzania’s 19,340-foot Mount Kilimanjaro in December.

It doesn’t end with mountains, either. Since setting the Summit America record, Huston has crisscrossed the country, sharing his message with corporate executives, churchgoers, medical conventions, schoolkids and anyone else willing to listen: Everybody is afflicted with something. Everybody goes through tough times. Everybody can go on.

“I want people to know that they can see their way through tough times,” says Huston. “This isn’t about an amputee mountaineer getting to the top of a mountain. It’s about changing lives.”

Of course, at times it is strictly about getting to the top of the mountain. When Huston and his crew arose that morning last June at their camp on McKinley, they knew they had been provided a narrow window of opportunity. Angry storms march across McKinley’s peak like rush-hour commuters pouring through a turnstile, preventing more than half of those who start the climb from reaching the summit. McKinley is also one of the world’s coldest mountains.

Huston and his climbing party had already met several teams that had turned back because of bad weather. They knew they had to move quickly to take advantage of the clear skies. They also knew they had a long day ahead of them. Experienced climbers take nine to 12 hours to make the scramble from 17,200 feet to McKinley’s summit and back when weather conditions are ideal. Vining had allotted 20 to 24 hours for the Huston party’s climb.

The ascent to this point had not always been easy for Huston. He had struggled to swallow thin air, to forget the extreme soreness in his stump and in his entire body, to ignore the anger and frustration of chasing his able-bodied team members up the mountain.

Now they were pushing toward the top. With the sun pouring down on them, the four climbers moved up the final ascent to McKinley’s South Summit, each man wrapped in his own thoughts.

Huston’s world had pinched to six words.

“I just kept telling myself over and over: Three breaths, step, stop and rest,” says Huston. “I didn’t know what all this meant, but I knew I had to get to the top. I also knew that if any mountain was going to knock us out, it was going to be McKinley.” It nearly did. Several times Huston fell in the sun-softened snow, and Vining watched quietly as Huston labored back to his feet.

Eight hours later they reached the summit ridge. Sunshine, brighter than anything Huston had ever seen, poured through the blue sky and spilled across acres of snow, radiating back in the sparkle of billions of ice crystals. Fat, puffy clouds mustered over the still, frozen world. Best of all, the climbers were at 20,000 feet, an easy 15-minute walk to the mountain’s peak.

As he stood atop McKinley, nine days after the start of the climb, Huston’s mind was a maelstrom. He felt joy and satisfaction. He made a light-speed recap of the previous months of effort. He faced the sobering prospect of the 5-1/2-hour descent to their camp followed by three days of climbing back down to the mountain’s base. The four climbers did an impromptu jig. Huston crows incessantly about the broad appeal of his message–that mountains, and far greater obstacles, can be surmounted by everyone. “Through climbing,” he says, “I am representing the struggle in all of us.”

Vining believes this, but only to a point.

“No doubt he has a mission to help others,” says Vining. “But I suspect this is something he has to do for himself, too.”

Ken McAlpine, a freelancer from Ventura, Calif., has written about a variety of topics for SI. Orginal Story

Energizer Keep Going Hall Of Fame

Daily Tribune: Bahrain

Success Before 30: Internat’l Youth Conference Bahrain

By Afnan Abdulaziz

Todd Huston is an amputee, author, world record holder and inventor, whose life is committed to inspiring others to be their best. With his journey of pain, determination, and adventure, including his expedition to the highest peaks in all 50 United States, others are able to overcome their challenges. His story helps everyone realize they too can reach new heights of well-being, success, and happiness.

To begin with, you have been well recognized for being an “amputee”. What does it refer to, and how did your injury occur? – When I was a 14-year-old, I was in a boating accident where my legs were caught in the spinning propeller and this eventually caused me to have my lower right leg removed. You have a radiating smile, this reflects your great insistence, what is your perspective on that? – How you feel and react to the circumstances of life come from you making internal decisions from within yourself and not from the external circumstances of the world. No matter what the circumstance, only you have the power to choose whether something that happens in your life is a blessing or a curse. We make these choices every moment of the day. What ignited the spark in you to make these significant changes and what strengthened your determination to succeed? – A realization that our power is not dictated by the external world, but by our internal world of our mind and spirit. Having a patented invention, how would you describe your journey towards reaching that accomplishment? – Whatever problem you may be facing in your life, is probably being experienced by many others. This is when you get to make the choice of whether or not you are going to create a solution or continue seeing it as a problem and hope someone eventually will create a solution. If not you, then who? I merely created a solution for myself that also helped many others that were missing a leg and needed a better performing artificial leg.

Todd, there is no denying that you have broken world records in climbing mountain peaks, did it at some point seem impossible to you?

– Yes, and at one point I stepped off the trail and thought about quitting. Then I remembered how important it was to accomplish the mountain climbing world record for myself and others. Sometimes we may make a mistake, be discouraged and get scared, that is when we pause, remember who we are and why we are doing something and get back up and keep moving and eventually we will reach our goal. It is impeccable that you would not have reached this safe zone if it were not for the hardship and difficulties you have faced in your life, coming to that, what is the toughest moments you have ever faced in your mission? – The toughest challenges are when I have had to face my own mind and recognize and overcome my fears. The belief in our own fears is our biggest obstacle in reaching our goals and becoming our best. Fear is nothing more than a shadow that we believe to be real, and we always have the ability to overcome it. In your career, what motivates you? – Love. I think that everyone has the same desire and goal to be loved and express love to the fullest extent possible. What career or paths you take in life are only details to your attempt to give and receive love. In your field, you truly are an inspiration to many people, what pieces of advice would you give others? – That everyone you meet, every situation you face in life is an opportunity for you to learn and uniquely express the greatness that is already within you.

An American speaker Todd Huston, who made an exceptional achievement by climbing 50 mountains across the United States of America, despite having an amputated leg. Huston achievement was featured in the Guinness world records.

Minister of Youth and Sports Affairs Hesham Al Jowder In a speech during the ceremony, Minister of Youth and Sports Affairs Hesham Al Jowder highlighted the support and care provided by His Majesty King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa to the youth and sports movements. He also underlined the concern of HRH Prince Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa, the Prime Minister and HRH Prince Salman bin Hamad Al Khalifa, the Crown Prince, Deputy Supreme Commander and First Deputy Prime Minister, in addition to HH Shaikh Nasser bin Hamad Al Khalifa, Representative of His Majesty the King for Charity Works and Youth Affairs, Chairman of the Supreme Council for Youth and Sports and President of Bahrain Olympic Committee. Minister Hesham Al Jowder pointed to the recent call of the General Secretary of the United Nations Ban Ki Moon to consider the youth as a priority in the developmental schemes of nations as they form a majority of the world’s population. HH Shaikh Nasser bin Hamad Al Khalifa presented mementos to the organizers and sponsors of the conference as a token of appreciation to their efforts. On his part, Minister Hesham Al Jowder presented a gift to HH Shaikh Nasser bin Hamad Al Khalifa for his generous patronage of the event. Read Full Article

Meet the Champion of Overcoming Adversity

Posted: 10:46 am, Sunday, April 20, 2014

Northeast Oregon Now

BY MICHAEL KANE

Todd Huston shows his artificial leg to the audience at the Umatilla Electric Cooperative’s 77th Annual Meeting at the Hermiston Conference Center Saturday night. Huston spoke about overcoming life’s challenges. Huston Tells Story of Climbing U.S.’s Tallest Peaks on 1 Leg

Todd Huston has overcome every challenge he has faced. From losing his job to losing his wife and even losing his life – twice – Huston has come out the winner every time. Adversity, it seems, is simply no match for the 52-year-old Oklahoma native.

And when life’s challenges weren’t enough, Huston created another seemingly impossible challenge – climbing the highest peaks in all 50 states in record time. Huston, who was the featured speaker at Umatilla Electric Cooperative’s 77th annual meeting Saturday night, accomplished the feat in 1995 in just 66 days, shattering the old record by 35 days. And, oh, by the way, he did it on one leg.

Huston was 14 when his right leg was torn up by a boat propeller. He lost so much blood that he overheard a doctor say, “I don’t think this kid’s going to make it.” And he almost didn’t. Doctors had to resuscitate him twice – once in the emergency room and again on the operating table. After his initial surgeries, the damage was so severe, doctors told him he would probably never walk again. But Huston is nothing if not determined. Even after his leg was amputated and he was fitted with a pathetic excuse for an artificial limb (Huston compared it to a tree limb with a shoe attached), he didn’t give up.

But there were moments of anguish when he would find himself asking, “Why me?” The answer didn’t come immediately. First, he had to learn to walk again. Then he became addicted to pain killers. At one point, he nearly overdosed before he found the strength – and desire – to kick the habit.

“When you really want to change something in your life, you can do it,” he said. “It only takes an instant to make the decision.”

That may sound glib and simplistic, but Huston said it really is the first step to overcoming any challenge one might face. After that, you have to delve deep into your soul for the strength to move forward.

“You have to look for something within you that is stronger than anything the chaos of the world can throw at us,” he said.

Huston overcame his addiction, worked to earn a degree in finance, got married to a New Zealand woman and settled into a happy, successful life. But adversity wasn’t through messing with Huston. In one particularly bad week, Huston came home shortly after losing his job only to find his wife was gone. It turns out, she had married him so she could remain in the United States long enough to obtain her U.S. citizenship.

By this time, however, Huston was getting pretty good at getting back up after being kicked to the ground.

“No matter how dark things get, there’s always something positive that will come,” he said. “Too many people focus on the darkness and make it part of who they are. Let go of the darkness and look for the good and it will show itself.”

Huston is shown here climbing without the aid of a rope during his 1995 expedition in which he scaled the highest peaks in all 50 states.

Huston left the world of finance and became a psychotherapist and clinical director of the Amputee Resource Center in California, working with others to overcome their own challenges. But Huston wasn’t done taking on his own set of challenges. One day, he saw an announcement of a planned expedition that was seeking physically-challenged people to climb the highest peaks in all 50 states. He immediately signed up and began training for what promised to be his most daunting challenge yet.

Then, one month before the expedition was to begin, the funding fell through.

“But I heard a voice in my head that said, ‘Do this climb on your own.’ Sometimes you have to step out of the box that you created. You know you’re much bigger than any box.”

So, Huston began selling T-shirts to raise the $50,000 needed to fund his own expedition. This, it turned out, was the easiest of all the obstacles Huston has ever faced. A wealthy businessman heard about Huston’s plan and was so intrigued and impressed by the idea of an amputee attempting to climb the highest peaks of all 50 states that he personally funded the entire expedition.

“I don’t know if he even got the T-shirt,” Huston said.

And so, with the help of some experienced climbers, Huston began his 50-state journey up and down the tallest peaks. Some were more challenging

than others. For example, the highest elevation in the state of Delaware happened to be in the middle of a city street. Alaska’s Mount McKinley,

however, proved to be much more difficult and much more treacherous. At more than 20,000 feet in elevation, the trek up the mountain was slow, arduous and dangerous.

“I could only take one step before I had to stop and take three deep breaths,” he said. “Then another step and three more breaths. Then another step and three more breaths.”

The climb was chilling in more ways than one. He and his fellow trekkers came across two bodies – climbers who died attempting to reach the peak. They had to dig deep pits in the snow to protect themselves overnight from hurricane-force winds. But they eventually reached the peak and completed the expedition is record time – and without the aid of ropes to protect them if they slipped and fell. Throughout the expedition, Huston encountered danger beyond the climbs themselves. There were rattlesnakes, bears, extreme weather (including 118-degree heat while ascending the 8,751-foot tall Guadalupe Peak in Texas) and, of course, personal fear.

Fear, said Huston, is what holds most people back from accomplishing their goals.

“Danger is real,” he said. “But fear is something we create within ourselves. Always recognize danger, work to minimize it and then move forward as best you can.”

And Huston is an expert on that subject.

World Record Holder Todd Huston Motivates Coast Guard Workforce

Mr. Todd Huston was the keynote speaker for CGHQ’s National Disability Employment Awareness Month (NDEAM) observance. Mr. Huston is a world-record mountain climber, who while boating with his family at the age of 14, was injured in a horrific accident as his legs were caught in a boat propeller. The traumatic injury led to the amputation of his right leg. As an amputee, he persevered, embraced the challenges in front of him, trained and participated in the Summit America expedition, setting a world record for climbing the highest elevations in every American state in less than 67 days. Pictured above, holding a mountain climbing pickax used to aid climbers, (left to right), Vice Commandant, ADM Charles Ray; Todd Huston; and the CG Executive Champion for NDEAM, RADM Erica Schwartz. By Ms. Deborah Gant, CRD, USCG HQ. Full Story

Inspirational person of the month May 2018!

Our inspirational person of the month is Todd Huston. After losing everything from his leg to his marriage and his house, Huston preserved to become of the greatest inspirational amputee mountain climbers in the US. Huston’s story of the power of love and inspiration is one for the books. In his book, More Than Mountains, he talks about what it was like to climb all 48 tallest peaks in the US and what inspired him to keep going.

When he was 14 he injured his legs in a boating accident and due to complications eventually had to amputee one leg below the knee. Huston went on to become a psychotherapist and clinical director of the Amputee Resource Center in California. Where he helped train healthcare professionals and wrote articles in working with individuals coping with disabilities.

One day he got a phone call that changed his life. After a failed marriage and losing his house and almost everything, Huston got a phone call asking if he would like to join the Summit America Expedition. This expedition would entail climbing to the highest elevation of all 50 states. Little did he know that this would lead him to break a world record. He achieved his goal and summited all the highest peaks in 66 days and 22 hours, beating the previous record by 35 days! Full Story

Huston now has a non-profit organization called Love the Power.com.

THE POWER of Thinking, Speaking & Acting in Love

TODD HUSTON: Workshop Learning to use love in every moment of your life in whatever you are doing. This workshop helps you find your passion, joy and power in your life, relationships, business and career, and your world by learning how you can give and receive the greatest amounts of love.